Please welcome my guest,

Saskia Walker!

#

When I started out on my writing journey I used to fret about how the fantasy or paranormal elements of a story would mesh with the more everyday aspects. As writers we want our stories to flow seamlessly for the reader, and for them to accept what is way beyond the norm alongside the more rational elements.

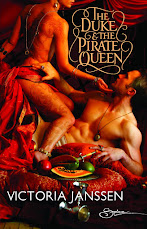

This is a skill that my hostess has, in spades! In Victoria’s novel,

The Duchess, Her Maid, The Groom and Their Lover, I found I accepted the more unusual aspects of the society she portrayed because the writing was so solid overall. For example, Victoria describes the Duchy palace, its furniture, art works, the costumes and surroundings, in such vivid detail that I readily accepted the more unconventional things that happen within this society. That is skilled world building.

A few years ago I took an online workshop by best-selling paranormal romance author

Angela Knight. Angela was talking about how to give your paranormal characters life and make them leap off the page. When she had a question and answer session, I raised my concern about making the fantasy elements mesh, so that they are instantly acceptable to the reader. Her response was to research and write the real-world elements solidly. For example, if your hero is a police officer who is secretly a werewolf, it's his everyday police world you need to get right, and the reader will go with the rest because she/he will be so grounded in the character and the story.

That notion began to sink in for me, and I was able to look at the issue from a different viewpoint. It also meant I worried a bit less and focused on getting the groundwork right instead! I think I’m getting there, at least I hope so.

In my latest novel-length publication,

Rampant, I had a lot of genre cross over to deal with, and it set up a number of “believability” challenges as a result. The story draws on the history of witchcraft in Scotland, and the very real persecution of those who were ousted as witches. The story is divided between a contemporary setting and a historical one, and in both settings several of the characters are secretly practising witchcraft. The rich paranormal folklore of Scotland and the history of persecution was something I was able to draw upon, as was my love of the natural world and the area I chose to set the story in, the East Neuk of Fife. What I had to mesh with that was my own world building, in particular, the magic.

To close, here’s an excerpt from a scene set in the historical world of

Rampant. In this part of the book it was important to get the period and setting right, as well as the atmosphere of suspicion and persecution, in order to ground my story and give it weight. See what you think.

#

The master is leading me into the forest. He waylaid me as I was on my way to pick summer berries and ordered me to leave my basket and to follow him here instead. His mood is not good. With one hand locked around my wrist he drags me alongside him, his handsome mouth tightly closed.

“Ewan, what is it? Whatever is the matter?”

He does not reply.

We follow the path to the place where the coven meet, but the brethren are not here with us now. It is just the two of us, and the master is like a stranger to me. His head is bare, his hat who knows where, and his necktie is askew. His hair is uncombed, and he looks as if he has barely slept.

Beneath the trees the scent is high for it rained heavily in the night, an early summer storm, and whilst it is fresh down by the harbor, up here in the trees the musky smell of damp undergrowth fills the air. The ground is muddy and the path is damp and slippery beneath my boots, sending me skittering on the path.

He does not look back, does not seem to notice. Why is he bringing me here now, and why does he not speak? My heart beats hard in my chest, for I have a dreadful bad feeling about this.

“Speak with me,” I plead, “tell me what it is that you need. I promise I will do whatever you want, if only would look my way and speak to me.”

Still he does not answer. Instead, he drags me even faster across the ground, intent on some purpose known only to himself. I can barely keep up, my footsteps stumbling in his wake, my skirts snagging on brambles. Then I see our own place up ahead, the clearing where our coven meets. The circles of rocks mark the five points where we have set our fires, and the earth is burnt from our rituals.

He stops walking and pulls me up short in front of him, strong hands wrapped round my wrists. I have to stand on my toes and stretch, for he seems determined that I look him directly in the eye.

“Feel my ire,” he urges, “know it in your soul.”

I do feel it, I see it and I feel it, a churning vat of pain that he wishes to share with me. Betrayal, there is betrayal there too, amidst the rage in his expression.

“I see it, my beloved master, but I do not understand.”

“I thought you had more sense, Annabel McGraw. You are fickle, as unruly as a bored child. I scorn you for wasting precious time, for inviting trouble upon the coven by dallying with villagers when you should be honing your skills.” He kicks half burnt logs out of his way before he pushes me down in the ashes.

My body hits the ground, my spirit fast feeling what he wants me to know—humility, shame. He is showing me how he could break me. That I could be as easily fated by him as a woodland creature or a captured bird that he would sacrifice for some greater purpose.

Clumsily I sprawl, charred wood and rocky earth rough beneath my back, my left leg twisted beneath me. As his chosen woman amongst the coven, I can think of no greater shame that he could bestow upon me.

I try to rise up on my hands, my emotions unsteady and my thoughts running this way and that as I try to understand his actions. I resent him for this. “Why do you try to shame me this way?”

He drops to his knees beside me and shoves me to the ground with his hand hard against my chest. I cry out when the rocks and stones dig into my back. His eyes blaze and his lips are drawn back from his teeth. His anger is overwhelming. I feel it pumping violently from the hand he has splayed at the base of my throat where the skin is bare. His palm is so hot it makes me squirm for fear of being branded by him, a demon’s mark that I know he has the power to bestow. And yet it makes me lusty, too, for he is so handsome when his immense magical power burns in his eyes this way.

“You have been foolish, risking our secret, risking so much for a roll with an oaf of a fisherman.”

Was that it? That he is jealous of Irvine? I cannot fathom it at first, for he takes lovers where he chooses and it has not bothered him when I have done the same. But I am delighted, too, and I begin to see how I can turn this.

“Why do you do this?” he demands. “Is it not enough that together we could own all of the magic in Scotland?” He closes his fist around the air in front of my face, and I see the immense light that glows from within it.

I watch, secretly delighted by his actions. I am almost gleeful that his need for me has driven him to express himself in forbidden magical enchantments. He opens his fist and the light swirls out into the atmosphere, sparkling with colors, before darting away into the trees…

If you’d like to read another excerpt from

Rampant, you can do so

here.

#

Thanks, Saskia! (Also, I am blushing because you liked

The Duchess, etc. Thank you so much!)